Accordingly, what Kant means by “noumenon” is far more complex, and subtle. Though it would be nice and simple to define the noumenon just as “that which causes the phenomenon”, this would implode the entire Kantian enterprise. Furthermore, because of the necessary agnosticism on the question, it makes as much sense to say the noumenon is the cause of the phenomenon as it does to say the noumenon is a dancing circus bear named Rodney. It makes no sense, then, to speak of a supra-sensible causality beyond any possible phenomenon. Furthermore, once Kant has placed time and space on the side of the phenomenon, it becomes unclear what we mean by causality when it is applied beyond the context of space and, especially, time. Causality, as Schopenhauer points out, is a category only legitimately applicable to phenomenon by Kant’s own admission. Kant does toy with this idea, or manner of speaking, but never when it counts, that is, whenever he is discussing the problem of the noumenon directly. That is the noumenon as cause of the phenomenon.

We would be sabotaged right out of the gate if we didn’t put to rest a very common way of talking about the noumenon that is, nonetheless, obviously flawed.

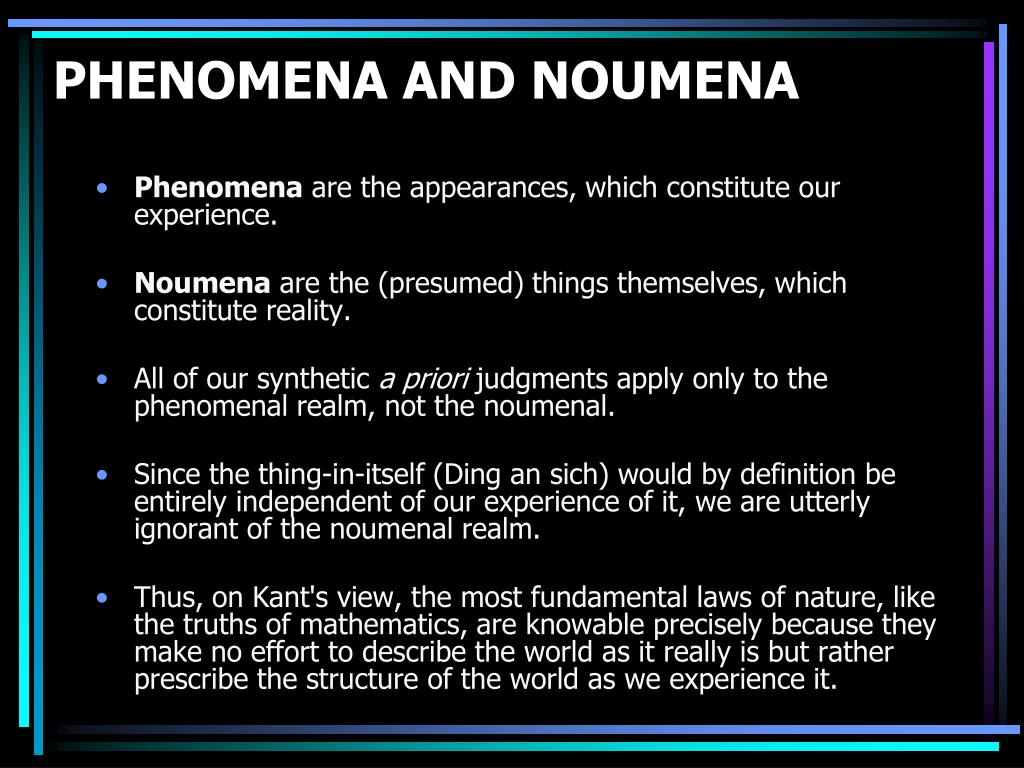

Obviously, owing to the definitional nature of the division, it is not a phenomenon, but the agnostic claim, and the division itself, need to emerge from phenomena. All we have at our disposal is the phenomenon, so for the noumenon as a concept to avoid a simplistic self-referential paradox, it needs to be explicated in the terms of phenomenal reality. That turns us back to the original question, then, which is What is the Noumenon? It cannot be what Kant divides the world into in a simple way, the way we would divide a genus into species. So, we should, instead, suspect the simplified account. The foolish thing would be to think that Kant has missed something so fundamental. How could have Kant divided the world into two parts and then gone on, with a perfectly straight face, to deny that we could have any knowledge of the second part? Isn’t the very division itself, and the agnostic claim about unknowability, presenting us with knowledge of what is unknowable? That is, hasn’t Kant, at the outset, committed a self-referential contradiction that any philosophy undergrad could spot with a blindfold on: “I know that the noumenon is unknowable”. What is a Noumenon? Ask any (philosophy) person on the street, and you’ll no doubt hear how Kant divided the world into the phenomenon and noumenon, and that we can’t know anything about the noumenon, but have to resign ourselves to dealing with phenomenon, things in themselves vs appearances, etc etc.īut even in this dismissive simplification an inconsistency has already emerged.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)